Additional pictures for download at the end of the text

Katrin Unger was born in Graz in 1986 and since completing her physics studies has been part of Anna Maria Coclite's research group at the Institute of Solid State Physics, where she is working on the development of tattoo sensors for the early detection of harmful pH changes in the skin.

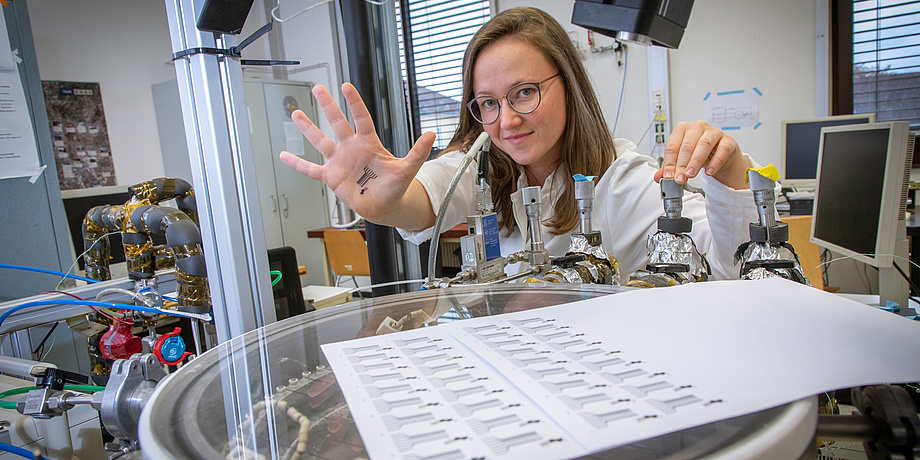

Combination of ink jet printing and chemical vapour deposition

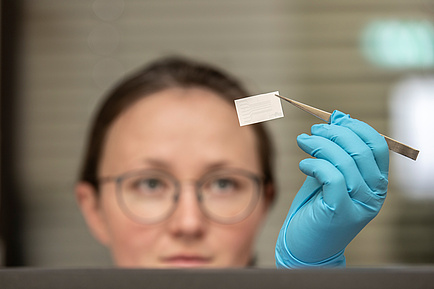

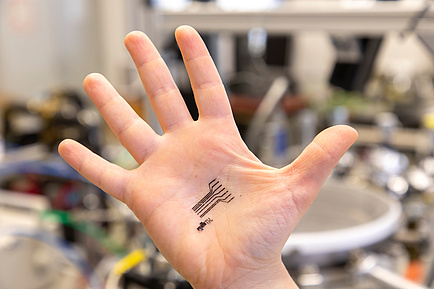

Using an ink-jet printer, Unger prints electrical conductors made of plastic with a resolution thinner than a human hair on blank tattoo paper, as known from children's tattoos. A polymer gel is then chemically evaporated onto these plastic electrodes in a vacuum. "Thanks to the vacuum-based method, we can work under gentle conditions and do not have to expose the substrates to high temperatures or solvents," explains Unger.

The evaporated gel layer is pH-active, i.e. it reacts to the pH value of the liquid surrounding it. Unger explains: "I use hydrogel, which can be imagined as a kind of sponge that absorbs water. Depending on the pH environment the gel is in, it absorbs more or less liquid, or in the case of the tattoo sensor, sweat, and thus changes the electrical properties of the sensor." This then provides information about the condition of the skin.

In her project, Katrin Unger combines the work of Anna Maria Coclite, who received the ERC Starting Grant for her Research approach for the production of smart artificial skin in 2016, with that of the working group led by Francesco Greco, who is developing printed tattoo electrodes for medical diagnostics.

Long-term skin monitoring

The average pH value of healthy skin is 5.5. The acid mantle that covers the human body is a barrier against viruses and bacteria. Environmental influences, diseases or medical treatments can change the pH value, destroy the protective coating and increase the risk of infection. Unger's tattoo sensors are designed to help diagnose these pH changes over long periods of time. And all this without disturbing the wearer: due to their composition, the tattoos move flexibly with the skin.

Sensitivity of polymers and adhesion of layers as a challenge

However, the path to application is still a long one. Sweat contains many different analytes that can act on the signal, making it difficult to clearly assign a pH value. Current challenges in Unger's research work are the improvement of the signal of the electrodes and the adhesion of the different layers. For an exact measurement – despite constant movement and stretching of the body – there must be no ablation from the tattoo to the electrodes, from there to the hydrogel or from the gel to the skin. "The tattoo sensor is supposed to be only a few micrometers thick in the end. Such thin layers tear easily and have to be treated carefully in order to establish contact with a measuring device," says Unger, who is building a bridge between basic material research and an application-oriented sensor with her project.

This research area is anchored in the Field of Expertise “Advanced Materials Science”, one of five strategic research core areas of TU Graz.