Run of the mill would be boring

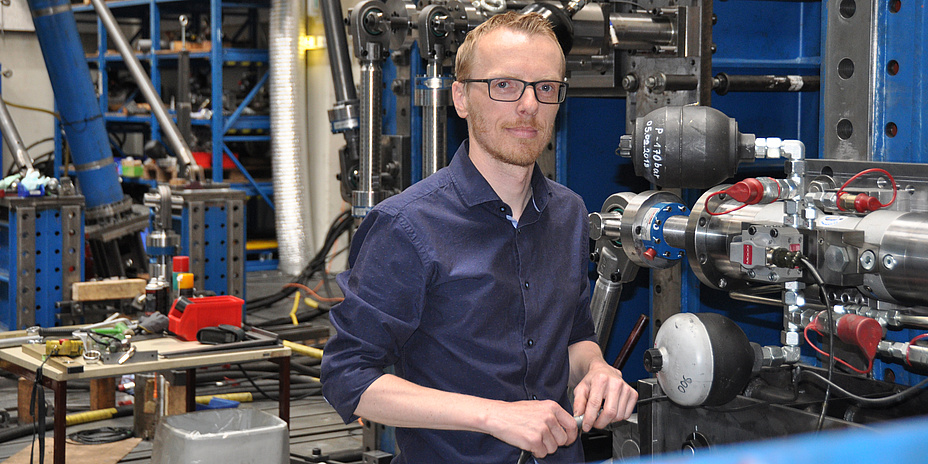

Peter Brunnhofer is Senior Scientist at the Institute of Machine Components and Methods of Development and head of the structural durability laboratory ‘Fatigue Testing Laboratory’ at Graz University of Technology (TU Graz). Since his doctoral thesis he has been investigating how structural components become fatigued due to cyclical loads.

News+Stories: You’re head of the Fatigue Testing Laboratory at TU Graz’s Institute of Machine Components and Methods of Development. Was this your professional goal?

Peter Brunnhofer: No, it just turned out like this. My first degree was in

<link _self int-link-internal>mechanical engineering and I then decided to pursue the branch of mechatronics engineering, where I studied measurement and control engineering in depth. Classical mechanical engineering doesn’t basically exist any more. Electrical engineering and control technology now play a crucial role in many areas of mechanical engineering. In any case work is constantly done in an interdisciplinary team. I find this generally positive at TU Graz – the fact that you can discuss something with so many people from different specialties in a simple and uncomplicated way. If there’s a problem, you can always ask the neighbouring institute. Anyway, my own plans after finishing my doctoral paper involved leaving university. But then my predecessor went into private industry. I was asked if I would take over the department and I took the opportunity of doing so because it’s an interesting and varied field of work.

The Fatigue Testing Laboratory is a laboratory for investigating structural durability. Tests include, for instance, how long a material or component can stand up to load which it is operationally exposed to. A cyclical or recurring stress is less favourable for a component than a constant stress.

What makes your job so interesting?

Peter Brunnhofer: Structural durability is characterised by the complex interaction of load, material, manufacture and geometry, and when developing new design methods both experiment and calculation come up against their limits. This results in a very multi-layered and fascinating field of activity. For this reason my work often takes me away from my desk into the laboratory, where I not only have to supervise test rigs, but also help set up the experiments when we’re short of man power. Mostly special test rigs are used in the Fatigue Testing Laboratory, which we have to develop and build ourselves. This is our strength at the Institute. Run-of-the-mill test rigs where the same old piece is tested, well that would be boring.

We’re currently developing a test rig on which electronic components from automotive engineering have to be exposed to an acceleration impulse of 10,000 g – 1 g is the acceleration due to gravity.

The job starts with concept development, then comes the classical mechanical engineering design of the parts, and then the measurement and control engineering, and finally the test rig is run and the test results are evaluated. Among other things, we’re currently developing a test rig on which electronic components from automotive engineering have to be exposed to an acceleration impulse of 10,000 g – 1 g is the acceleration due to gravity.

You didn’t just graduate from your studies, but also passed your entrepreneur certificate and got your international welding engineer certificate. Why is that?

Peter Brunnhofer: The international welding engineer certificate is an internationally recognised proof of competence regarding design, production and verification of welded connections – although it’s not actually about being able to weld yourself. Welded joints and their effect on the material, and consequently on the strength of a component, are an important topic in structural durability. The University already offers most of the necessary courses in its

<link _self int-link-internal>mechanical engineering studies. A final training course and test is held by the Schweißtechnische Zentralanstalt (SZA), an authorized national body of the International Institute of Welding (IIW). This training course is also offered at the Business development institute WIFI, but it is much more expensive and cumbersome. TU Graz offers its students a range of possibilities and services. I would certainly recommend students to do it. I gained the entrepreneur certificate in a cooperation between TU Graz and WIFI. Among other things there, I got to know the overall conditions of apprenticeship training, which is beneficial because we’re training two apprentices at the Institute.

When you’re not actually at the Institute and not undergoing a training course, where do you like to be, best of all?

Peter Brunnhofer: In general sport is very important to me to balance out my work. In winter I go ski touring or just skiing generally. Unfortunately I couldn’t fit in the new skis this year (glances at the new touring skis without bindings in the corner of the office). On top of that, I like to go running, cycle racing or climbing – especially bouldering.

What is bouldering?

Peter Brunnhofer: Bouldering is principally climbing with high grades of difficulty on small rock formations or artificial rock walls without the use of harnesses and ropes at high grades of difficulty and some very strength-demanding moves, in contrast to climbing parks or multi-rope routes, where the challenge is more in the area of endurance.

Just as the body becomes tired from workout, a component also goes through different phases of fatigue when it is under strain. An important issue in our experiments is detecting the relation between amount of strain and number of bearable load cycles.

So now we’re back to structural durability?

Peter Brunnhofer: Yes, in a way we are. Just as the body becomes tired from workout, a component also goes through different phases of fatigue when it is under load. An important issue in our experiments is detecting the relation between amount of strain and number of bearable load cycles. It makes a big difference in component sizing whether a component is designed for ‘a few’ load cycles or whether the load has to be sustained permanently. And it is exactly in this fit-for-purpose component design that there is a major potential regarding lightweight construction.

What happens during structural durability tests?

Peter Brunnhofer: Despite the latest software and increasing computing power, a lot of things can theoretically only be calculated with a certain amount of vagueness. To provide proof of the structural durability of materials and components, it is necessary to do experiments. By using test rigs, we determine material characteristics for the purposes of calculation on the one hand, and use experiments to check our methods and models. Experiments continue to occupy a very important position since technology is a very empirical science (smiles).

So what goes on in your test rigs?

Peter Brunnhofer: Work ranges from small material samples to bogie frames – in other words, the supporting structure of railway vehicles. We’re currently assembling a test rig for an structural durability experiment for a lightweight-construction frame. The ambitious goal of this development was a weight reduction of 50 per cent. Siemens was able to make savings of 48 per cent through a completely new approach. My colleague, Christian Moser, was invloved in a leading role.

Through the method development and relevant material and component experiments we’ve manged to contribute to making this lightweight construction approach possible.

In other words, this is a prototype?

Peter Brunnhofer: Exactly. The bogie frame for which we’re in the middle of building the test rig here is a prototype, not a series product. Through the method development and relevant material and component experiments we’ve manged to contribute to making this lightweight construction approach possible. Even if it’s not a series product, it has to be experimentally investigated in the lab so that approval can be given for trials on railway lines according to a wide range of standards. The primary task of bogie frames is to support the rail-car body and to guide the vehicle over the wheel-set axle on the track. The frame is a weight-bearing and connecting element and is therefore very important for safety.

What are you currently conducting research on?

Peter Brunnhofer: At the moment I am less involved in research than in the field of organisation. We are going through a period of upheaval in the lab at the moment. On the one hand, the topic of work safety is becoming increasingly important, and particularly in the lab there lurk a whole number of potential dangers. This is a huge area. On the other hand, we want to get ourselves accredited according to ÖNORM EN 17025. This is a certificate of competence for laboratories in a management and technological area. On top of this, in close coordination with Siemens and other industry partners, we’re planning a brake test rig for railed vehicles. We’ve been working together with Siemens very well for a long time here at the Institute, something which led to Siemens and TU Graz contractually sealing their cooperation in the Center of Knowledge Interchange (CKI) in 2015.

In the framework of the Center of Knowledge Interchange (CKI), the Structural Durability and Railway Technology working group at the Institute of Machine Components and Methods of Development work together with Siemens AG on many innovative projects in the area of design of modern railed vehicles. Other research areas include image processing and software engineering, and the fields of communication networks and communication technologies. Joint initiatives, activities and projects are coordinated in a coordination office headed by Christine Schichler in the Research & Technology House of TU Graz. Researchers and their partners at Siemens present their current research projects at the annual CKI conference. The so-called ‘Siemens class’ consists of young researchers at a variety of institutes at TU Graz who are working on doctoral theses commissioned by Siemens. The CKI coordination office organises a regulars’ table to promote contact between them.

Kontakt

Peter BRUNNHOFER

Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn

Institute of Machine Components and Methods of Development

Inffeldgasse 25D

8010 Graz, Austria

Tel.: +43 316 873 1380

peter.brunnhofer@tugraz.at