“My grandmother was just great.”

You are both working in the same field, but at different points in your careers. What led you both to physics?

Birgitta Schultze-Bernhardt: For me, I realised I wanted to study physics when I was still at school. My academic career just happened. I have been at TU Graz since 2013 and have held my chair since 2022. My research group is working on a spectroscopy method that sounds very abstract. But we are currently developing it further for issues relevant to everyday life – for example, so that we can measure and characterise the air quality in Graz.

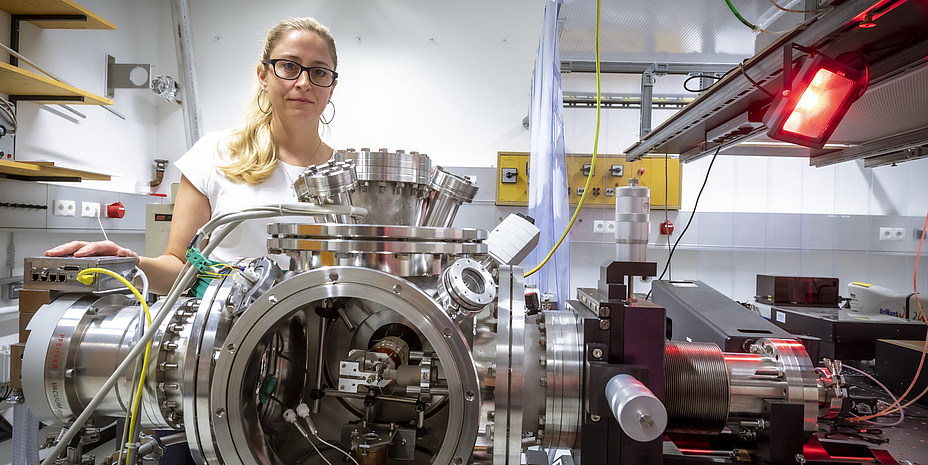

Anna Karner: For me, I also realised I wanted to study a technical subject when I was at school. I attended a technical secondary school (HTL) for civil and environmental engineering and I loved maths. I studied and graduated in civil engineering and physics at Graz University of Technology (TU Graz). After that, I worked in the private sector, but I wasn’t able to apply the knowledge I gained during my studies enough. That’s why I moved back to TU Graz and am now doing my doctorate in experimental physics. I work in the field of optics and we develop optical components for extreme ultraviolet light.

Would you like to stay in university research?

Karner: It would certainly be an option. But I am a mother and would therefore like to stay in Austria, where my partner also lives and works. For a habilitation, however, it is almost compulsory to work at a different university abroad. This is no longer as easy today as it was without a child.

How did you do that, Birgitta?

Schultze-Bernhardt: I’m the mother of three children who were all born in different countries. In academia, you are very flexible when it comes to organising your time and it is helpful if your partner is, too. I know many couples with children who both work in academia. It’s easy to take turns if the daily routine can be organised in a similarly flexible way. TU Graz is very progressive and dynamic when it comes to compatibility of career and family. Childcare is also a major issue.

Karner: TU Graz is already doing a lot in this respect with the nanoversity. But if I go abroad, that box should also be ticked there.

Schultze-Bernhardt: Today, childcare is also sometimes offered at conferences. Ten years ago I wasn’t even allowed to enter the grounds because I took my child with me when there was no other way. Fortunately, a lot has changed.

Did you perceive the academic careers of your female and male colleagues very differently?

Schultze-Bernhardt: As a woman, you have to do a lot of juggling. I find it impressive that Anna is doing her doctoral thesis as a mother. I couldn’t have imagined that. But my male colleagues all became fathers during this time; we few women didn’t have any children back then. It is certainly still in our heads that the woman is primarily responsible for very small children. Of course, there are also biological reasons for this, because the father simply can’t take on a lot of things.

Are longer absences such as parental leave a problem in academia?

Schultze-Bernhardt: If you stay away for more than half a year, it’s very hard to catch up and stay competitive. I never went more than half a year without doing research. Also because I enjoy research just as much as having a family. I didn’t want to stay away that long. Especially after the birth of my third child, it was a very exciting phase in which I built up my working group.

Karner: The work culture is also very important. We are not expected to work at the weekend and it’s okay if I leave early because the crèche closes.

How do you perceive the issue of leaky pipelines? – the fact that women very often leave university research at a certain point in their scientific careers?

Schultze-Bernhardt: The proportion of women in my studies was around 20 per cent – something I didn’t question at all at the time. But at some point I realised that I hadn’t seen a single female physics professor. Maybe they were there, but I didn’t have a single one in my lectures. During my time in the USA, I perceived things differently. There were still fewer women than men, but the proportion was greater. But the fact that we are talking about this topic today is an important step and shows that something is happening.

Karner: The only female professor I had in lectures during my studies is sitting next to me right now. There are still not very many women. I am currently the only woman out of 20 doctoral students. A colleague graduated in autumn, but is now also pregnant so a postdoc is currently not an option. I’m still not sure whether I will stay because I don’t know yet how I can combine my career with my family.

So starting a family is still an obstacle?

Schultze-Bernhardt: Yes. It was also very stressful for me at the time. I went to California on a two-year contract, then back to Munich on a one-year contract and then to Jena on a temporary junior professorship. You have no prospects for the future and don’t know what’s going to happen next. Everything went really well for me and I wouldn’t have wanted to miss out on the experience. I wouldn’t change a thing. But at the time, I really struggled with the academic concept.

So is it more of a mindset issue and women should just dare to do it?

Schultze-Bernhardt: On the one hand, yes. But on the other hand, of course, it cannot be denied that women are additionally burdened by this insecurity. As an experimental physicist, I may have built up a certain tolerance for frustration during my doctoral thesis (laughs). I learnt back then that if something doesn’t work out, it’s always important to have a plan B. We know that there is not just one right way.

Are role models important? And do you have role models?

Karner: Women like Marie Curie are particularly inspiring. She is one of only two researchers ever to have received two Nobel Prizes. And this at a time when women in science were still viewed with scepticism. But I also met so many inspiring people at university who are hard-working and smart. I admire that.

Schultze-Bernhardt: Not in science. But my grandmother was my role model. She couldn’t even finish primary school because she had to help out in her parents’ inn. But she got very far on her own and even managed a post office at some point. She was incredibly strong, smart and calm, and I often think of her when I need those skills. She was just great.

How would you organise the academic system if you could choose?

Schultze-Bernhardt: Help during the transition from a childless career to a career with children would be particularly important for young female scientists. That is a huge turning point. Especially if you are travelling with a small child. You first have to get used to switching between the role of scientist and mother. And it is important to create a family-friendly atmosphere. Fortunately, I’ve never had a problem with taking my children to a meeting out of necessity. On the contrary, everyone always found it a nice change from everyday life.

Karner: Fair pay during the postdoc phase would also be very important. If your partner leaves their job and goes abroad with you, it would be great if you could at least finance your flat and your life from your salary. This works quite well in Austria, but it is hardly possible in other countries.

Kontakt

Birgitta SCHULTZE-BERNHARDT

Univ.-Prof. Dipl.-Phys. (Univ.) Dr.rer.nat.

schultze-bernhardt@tugraz.at

Anna KARNER

Dipl.-Ing. Dipl.-Ing. BSc BSc

anna.karner@tugraz.at

Institute of Experimental Physics

Petersgasse 16