Do We Trust the Invisible Assistant?

Man-machine interaction

Even though a driver assistance system supports the driver on the road, the ultimate control of the vehicle still lies with the human driver. Cornelia Lex adds: “We are dealing with the entire range of human behaviour here. This is why it is important that driver assistance systems do not stress out the human driver and take into account personal modes of behaviour.” The human driver’s trust is crucial for an optimal interaction between the human driver and the driver assistance systems, and for an optimal task execution by the system. For example, with the “adaptive cruise control system (ACC)” the car automatically selects the appropriate speed to keep a safe distance to the vehicle in front. But the driver’s judgement whether this distance is big enough, and whether the vehicle puts on the brakes at the right time, is a subjective perception which in turn strongly affects the trust in the system.MueGen Driving

Starting with this premise, the MueGen Driving project, subsidised through the FEMtech tendering channel of the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG), investigated how drivers use the assistance systems differently and whether, up to which point and when they trust them. The basic parameters contemplated by the study were age, gender and driving activity. “Of course we could have looked at more parameters, but then we would have needed a very high number of test persons to come up with meaningful results,” comments Eichberger. From the very beginning, the project was competently supported by human factors expert Ioana Koglbauer from the Institute of Mechanics, a psychologist specialised in the interaction between man and machine. In her line of research it has become established practice to carry out usability tests with representative user groups: “It is imperative to gain knowledge about the perceived advantages and disadvantages of the application of technologies by all relevant customer groups.”It is imperative to gain knowledge about the perceived advantages and disadvantages of the application of technologies by all relevant customer groups.

The study focused on two assistance systems: the safety-relevant Automated Emergency Braking System and the comfort-enhancing adaptive cruise control system. “It was our specific intention to start with simple systems that are already available as standard features in vehicles,” says Eichberger. The investigative approach started with an observation of the test persons in a real environment. The participants were asked to drive a series vehicle equipped with these systems – an adapted Audi A6 – on the road. “Of course you have to do this systematically. There is no comparative value or meaning in having people drive around just like that,” says Eichberger. “Therefore, we looked for other tests with the assistance systems and selected typical driving manoeuvres from the specifications, told the test persons to carry these out and then proceeded with the evaluation.” The input for this evaluation came firstly from a questionnaire presented to the test persons, and secondly from objective measured data such as speed, acceleration and similar. “For example we asked the test persons to objectively assess the distance to the car in front, then we compared their statement with the objective data,” Eichberger adds.

All senses deceived

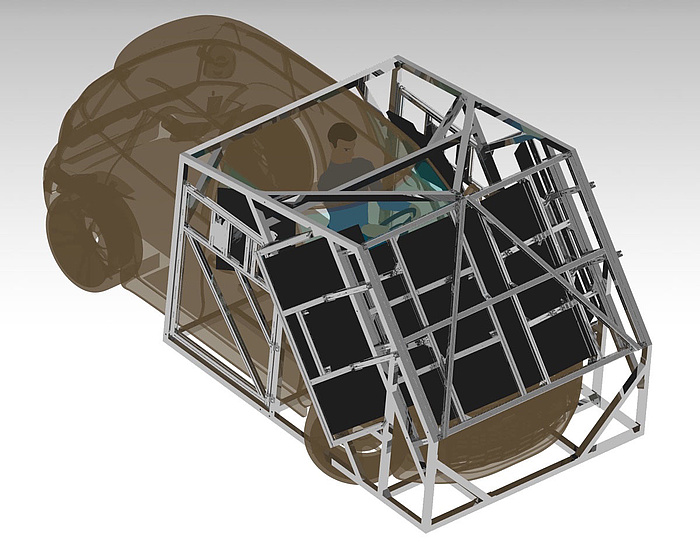

The second part of the research project called for a new development. If the test involves a much larger group of test persons, a real-life test is a time-consuming, risky and costly exercise. Therefore, the researchers decided to develop their own driving simulator at TU Graz – a task that took them one and a half years – to be able to carry out the experiment with a larger set of test persons under always identical conditions. “It is not that such a simulator is not available off the shelf but we thought this would have been too boring, and of course if you choose this shortcut you cannot install extensions specifically for additional research projects later,” Eichberger grins. For the simulator they converted a Mini Countryman, integrated it in a completely darkened and acoustically insulated box, and fitted monitors showing the simulated road on all windows.

A glimpse of the future

“It would be possible to make assistance systems react differently, depending on whether the person behind the wheel is a man, a woman, an older or a younger person,” Eichberger says looking ahead to future applications of the research results. He adds: “A higher level of trust will also push up the acceptance and satisfaction ratings, which will automatically benefit safety.” All participants in the research project are already working on follow-up projects that study the subject in even greater depth.

This research area is anchored in the Field of Expertise "Mobility & Production", one of five research foci of TU Graz.

Kontakt

Assoc.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn.

Institute of Automotive Engineering

Inffeldgasse 11/II

8010 Graz

Phone.: +43 316 873 35210

<link int-link-mail window for sending>arno.eichberger@tugraz.at