How do you make proteins?

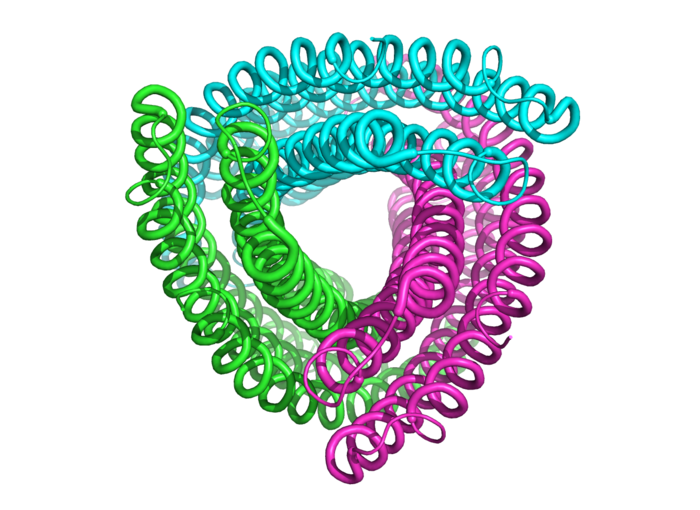

Green, pink and turquoise party streamers dance across Gustav Oberdorfer’s screen, tracing more and more new shapes. But what look like cheerful decorations are actually complex models of amino acids, intertwined in a seemingly endless range of combinations. Since February 2018, Oberdorfer has been a university assistant at TU Graz’s Institute of Biochemistry, where he designs proteins using simulation software. What we can see on-screen at the moment is a program called Rosetta calculating folds in an amino acid chain.

Protein folding

Proteins consist of chains of amino acids. Folded into one another, they create the structure of a protein, which often determines its function. Amino acid chains fold to make the structure with the lowest amount of free energy. But in order to find that structure, researchers must analyse countless variants of different types of folding on a computer. “If a protein had to try out all of the possible combinations during the folding process, it would take longer than the time for which our universe has existed,” Oberdorfer explains. Known as the protein folding problem, this means that predicting protein structures, let alone designing them, has long been a purely theoretical question.

However, a number of parallel developments have rapidly accelerated the pace of research in recent years. “We have more processing power available, the algorithms used in the simulation programs are getting better all the time, and the synthetic DNA fragments used to produce artificial proteins in the lab are becoming cheaper – they can even be manufactured using a process similar to inkjet printing,” says Oberdorfer enthusiastically. “Now we can carry out large-scale testing of synthetic proteins. For instance, researchers can search specifically for a protein that binds the influenza virus.” So computer-aided protein design has opened up new approaches to solving biotechnological and biomedical problems.

Not a party streamer, but the structure of an amino acid chain.

Oberdorfer’s dissertation was about amino acid chains and folding. He took part in a project that investigated the way in which bacteria produce the antibiotic nikkomycin. This happens in part thanks to the protein NikO – and it was the young researcher who identified the protein’s structure. Oberdorfer sees his current work as the logical next step: “Structural biology and protein design are two sides of the same coin.”

Filters and cavities

At the moment, Gustav Oberdorfer is heading up two research projects at TU Graz. As part of an Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project, the hunt is on for non-naturally occurring protein structures with cavities in their centres. These can serve as a filter and could be used to remove toxic substances such as mercury from water, for instance.

The NAWI Graz graduate’s second project was awarded a prestigious ERC Starting Grant by the European Commission. Together with his team, Oberdorfer aims to produce proteins with cavities that can bind a specific small molecule and subsequently catalyse a reaction. “We don’t just want to answer a particular question, but develop a general method that can be used to produce such proteins,” Oberdorfer emphasises. “We’ll see whether we can do that or not. Maybe there isn’t even an answer to this question, but we’ll never know if we don’t try.” His team is looking at specific applications, one of which involves trying to bind and break down the pesticide glyphosate.

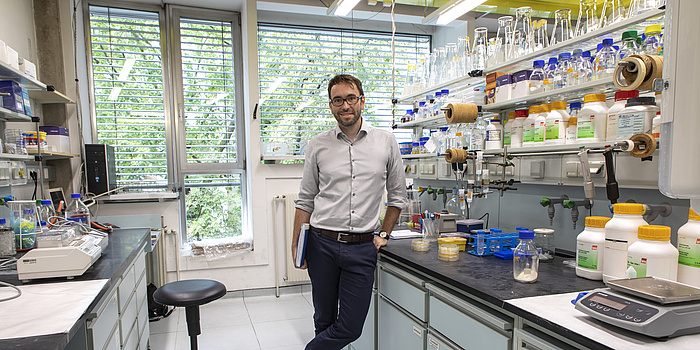

At work, the 36-year-old splits his time between the office – designing proteins on the computer – and the lab, where he tests artificial proteins. The latter is the most important aspect for him, “because up to that point, everything is just a theoretical construct.”

Graz – Seattle – Graz

Born in Styria, Gustav Oberdorfer was also an undergraduate in Graz. After obtaining his degree in molecular biology at the University of Graz, he went on to complete a doctorate in molecular enzymology with NAWI Graz, studying at the Institute of Molecular Biosciences at the University of Graz and TU Graz’s Institute of Biochemistry. He then moved abroad, spending four and a half years in the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington in Seattle, one of the leading research institutes in the field; Oberdorfer was familiar with the university after a six-month research visit while writing his dissertation.

“The time I spent in the USA has been the most productive and interesting phase of my research career so far,” he recalls. “I worked with over 80 people in a big laboratory. It was an extremely creative environment.” The effective collaboration was down to two basic principles. “First, we had access to all the findings of all researchers. So you can use and build on other people’s insights – I found this approach totally unique. We called it ‘leapfrogging’ – you jump forward a couple of steps in the development process because you can make use of existing findings. Second, one of the priorities was ensuring the working group was as diverse as possible – from a professional and a cultural perspective.”

Gustav Oberdorfer in the lab where he tests artificial enzymes.

Although it was initially hard to readjust to life in Austria after such a rewarding stay abroad, Oberdorfer now feels totally at home. “Students here receive better practical training and the universities have outstanding facilities.” He also teaches at TU Graz and gave his first lectures here. “That was a totally new experience, giving lectures as opposed to working with students on practicals. But the lectures are great fun, I enjoy working with the students.” Anyone interested in finding out first-hand about Oberdorfer’s research focus will soon be able to attend his new Protein Design lecture.

The great outdoors

Outside work, Gustav Oberdorfer enjoys mountaineering and travelling – he has been on a three-week cycle tour of Iceland and trekking in Nepal – as well as music, and he plays bass guitar in the band Musikcafe Prenner. Music tip: the band’s EP “Raus aufs Meer” (“Out to Sea”) came out last autumn.

This research topic is part of the Field of Expertise (FoE) Human & Biotechnology, one of five research focuses at TU Graz. News on research in the FoEs can be found at Planet Research.

Kontakt

Gustav OBERDORFER

PhD

Institute of Biochemistry

Petersgasse 10–12/II | 8010 Graz

Phone: +43 316 873 6462

gustav.oberdorfer@tugraz.at